‘Blinded By The Light’ Film Review: The Reluctant Artist Pays a Tortured Homage to His Art

By Edisa Yeo

I watch films for fun and mostly, just the ones which are available on streaming platforms or in a cineplex.

I offer up the above unsentimental statement because Blinded By The Light, a short documentary about Thailand’s rich and grand cinema history, seems to solicit it. The film is a compilation of voiceover testimonies from a number of Thai people who have worked on film sets. For a film about filmmaking, it is markedly reticent about its subject. In between confessions of love for the art form, the film procures more prosaic accounts, like –

“I just don’t find any [of the films I’ve watched] to be particularly great or life-changing.”

However, the film playing out its own self-deprecation actually frees us up of any instinct to disparage art-making ourselves. Because it is the perfect picture of self-abnegation, we feel indignant on its behalf when the value of filmmaking is thrown up against images of war and economic hardship. Soon, we come to an understanding that the legacy of filmmaking in Thailand has never escaped this sense of insecurity, in every meaning of the word.

In fact, the feeling of ambivalence and detachment towards filmmaking finds significance in the split-screen format of the film.

At every turn of images, we find it almost impossible to draw meaningful associations between the images placed next to each other. This even destroys one of the basic tenets in filmmaking – The Kuleshov Effect – which is the idea that two shots in sequence will produce more impact than a single shot. Down to its very sutures, the films almost resist wanting to be made into a Film.

We sense that this is so because the filmmaker is actually hesitating to put together a film. The most interesting thing that Blinded By The Light creates is this feeling of real fear and danger around the endeavour of creating a movie. And the way it does so through the motif of the occupational hazard is truly innovative; not just because it grounds the melodrama of “suffering because of one’s art” in flesh and bone, but more importantly because it spotlights the people for whom filmmaking is but a job – the manual labour workers on set.

Crew accident on set

The film narrates a few cases of accidents suffered by crew members on set: automobile accidents, back injuries from heavy lifting. Meanwhile, the spectre of what happened to the two most beloved stars in the Golden Age of Thai cinema drifts quietly on and off the screen, without narration.

Mitr Chaibancha, Thai Star who tragically died from a helicopter accident while filming

Petchara Chaowarat, starlet who went blind from spending so many hours exposed to bright set lights, and whose affliction is the namesake for the film.

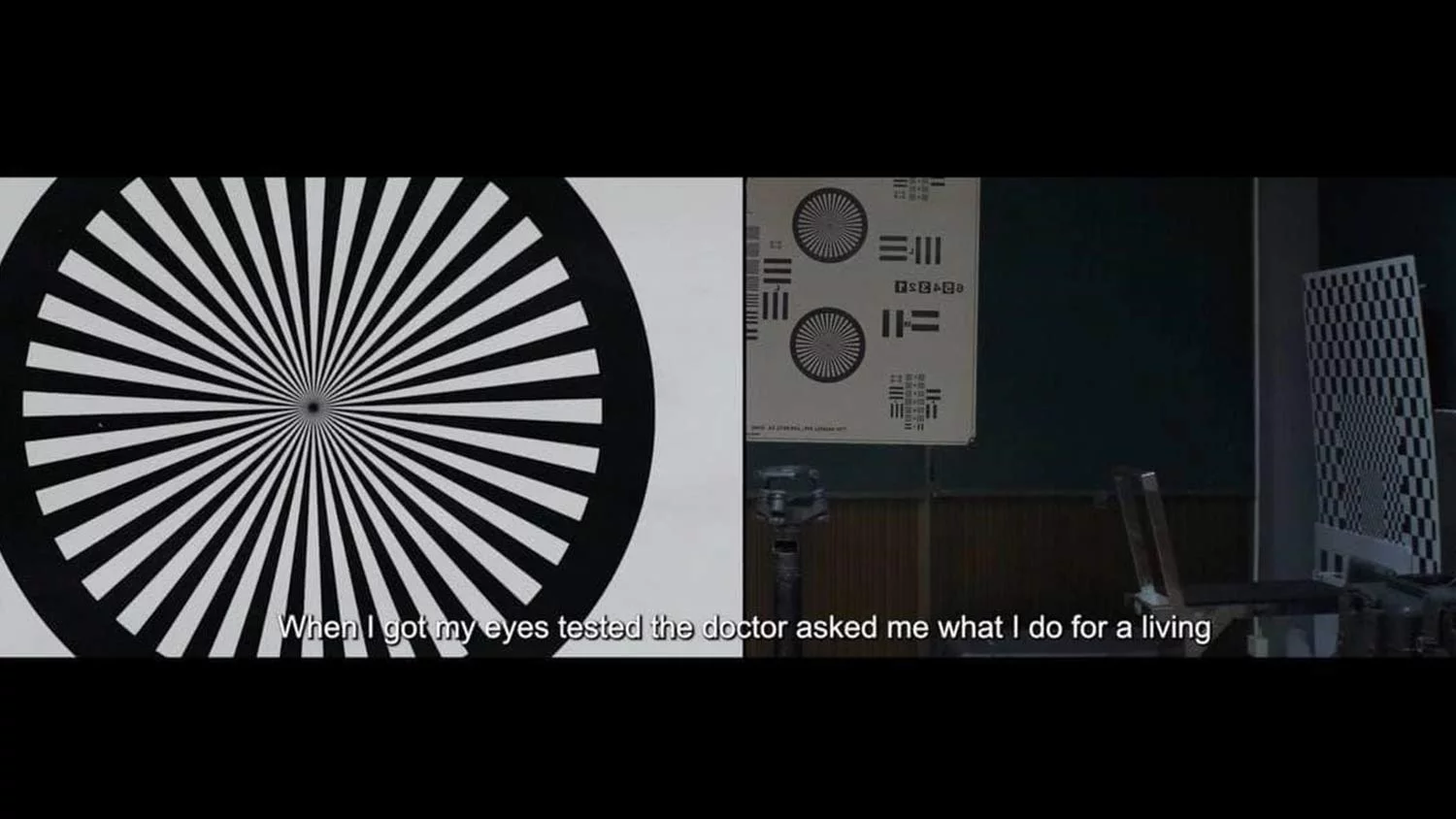

The final segment in the film consists exclusively of non-archival footage and appears to be from the point of view of the actual filmmaker. It is time for him to submit his own reflection on film. At the start of the sequence, both screens start to capture the same image, but one appears more stylized than the other. One screen represents what he is actually looking at, while the other is his allusion to his ‘filmmaking eye’ – the part of him that can no longer see in the same way as before.

“When I got my eyes tested the doctor asked me what I do for a living because my eyes are too different from each other.”

Briefly, the film lingers on images of shadows, as if turned away from a light source. We wonder if the filmmaker has resigned from a perilous life of movie-making. But right before the film ends, the camera cuts to the sun in the sky. The filmmaker faces up to the light as a brave moth ventures toward a flame.

For him, it is the only way he sees, the only way he is seen.

Final shot of Blinded By The Light