Portraits Of Faces On A Screen In ‘Himala: A Dialectic Of Our Times’

By Krystalle Teh

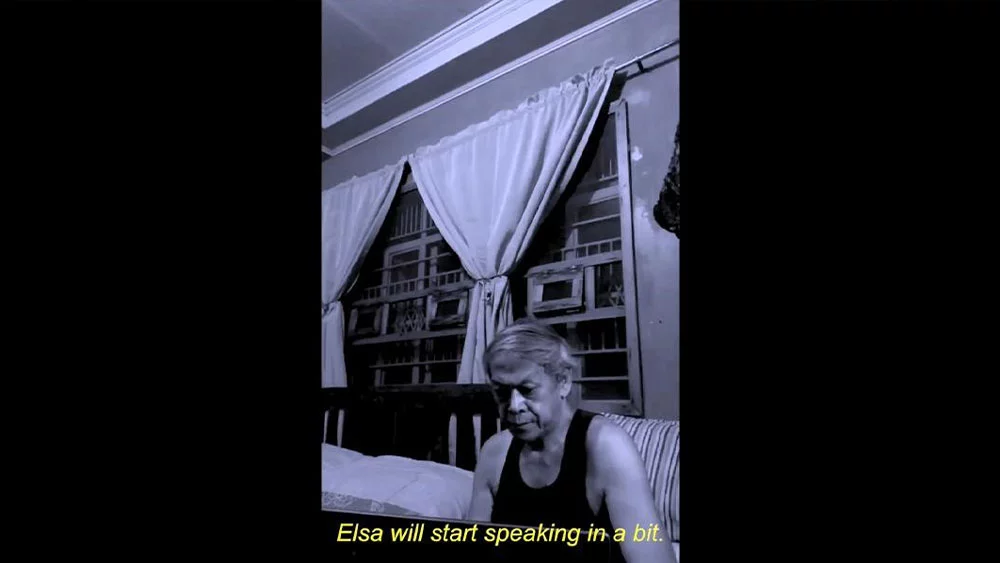

1. Grey-streaked combover, eyebrows arched as if in perpetual judgement. A man sits in front of a laptop screen in his home, the curtains pulled back against a window. He’s framed in a black-and-white portrait shot that’s been filmed with a phone camera, likely by the man himself.

In Lav Diaz’s eight-minute short film Himala: A Dialectic of Our Times, twenty-eight faces flicker before the screen, ostensibly reacting to the voiceover that follows. It is the impassioned polemic that Elsa, the messianic figure of the film Himala (1982), delivers to her devotees just before all hell breaks loose: ‘Walang himala. Ang himala ay nasa puso ng tao.’ (‘There are no miracles. The real miracle is inside the heart of man.’)

2. Though we hear Elsa’s voice, which is unflinching in its conviction, we never see her face beyond the film’s non-diegetic monologue. And yet it is her face, in its conspicuous absence, that casts a shadow upon Diaz’s film.

During an early scene in Himala (1982), Elsa encounters an apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary during a solar eclipse. This vision is the basis of her claim to divinity as a faith healer. The wind sweeps her hair across her face, her eyes gloss over in a state of rapture. Her face is overcome by a profound yearning that is poignant and persuasive, though we never see what she sees.

Throughout the film, the actor Nora Aunor plays her as elusive and hard to read—at once triumphant and tragic, liar and victim, false prophet and true saint. So woeful is her performance of virtuous female suffering, so feverish her religious ecstasy, that the line dissolves between truth and delusion.

By Himala’s tragic end it turns out Elsa has deceived her followers all along. As Diaz’s film advances grimly towards Elsa’s stunning disclosure, as overheard in the voiceover, it becomes clear that his film commits a similar act of deception too.

To careful viewers and long-time Diaz acolytes, most of the faces we see on screen are unmistakably those of Diaz’s cast regulars such as Shaina Magdayao and Pinky Amador. Like in Elsa’s vision of the Virgin Mary, we are led to believe that the actors are watching Himala (1982) though their screens are never revealed on camera. The possibility that the entire set-up is a ruse hovers in the background, even as the film’s parade of faces, with their shades of solemn emoting, elicit genuine affect. It’s a narrative sleight of hand that calls attention to the act of seeing and personal subjectivity, themes it shares with Abbas Kiarostami’s Shirin (2008).

In Shirin, more than a hundred actresses are filmed watching an adaptation of a mythical Persian romance that takes place entirely off-screen. Its conceit, which pushed the boundaries of narrative filmmaking at the time, is that the adaptation never happened and that the actresses had been asked to imagine scenes from their favourite films.

While the concluding intertitles of Diaz’s film may denounce a prevailing culture of lies, the film’s formal interplay of fiction and reality emphasises cinema as artifice and manipulation. Himala (2020) is, then, a paradox capable of both revelation and deception—not unlike its subject Elsa. In the dialectics of our time, wherein lies the distinction between filmmaker and false prophet? And, like Elsa’s devotees, are we as the audience equally susceptible to our consumption of the moving image and its inherent fictions? Are we prone too to the dangers of blind faith?

3. If cinema in Diaz’s hands turns out to be the ultimate act of deception in Himala (2020), what then is its legacy?

Among the faces on screen is that of the actor Hazel Orencio. In Diaz’s earlier film From What Is Before (2014), Orencio plays the character Itang, the sole caretaker of an intellectually disabled sister who is forsaken by the world at large. Often, she appears on screen as a diminutive or distant figure. Like most of the characters in Diaz’s allegorical epics, the humanity that Itang stands for is but a mere brushstroke on the film’s broad canvas, surrounded as she is by the immense forces (historical, societal, spiritual) that conspire against her.

It is surprising then to find Orencio framed in a semi close-up shot in Himala (2020)—a marked departure from Diaz’s usual tableau vivant compositions. Her hair is dishevelled, her eyes unblinking in their look of concentration. She is transfixed by the screen before her and appears to yield entirely to the notion of the moving image, though we know by now that this is a contrivance. Filmed during Luzon’s community quarantine due to Covid-19, the camera’s hyper-focus on the individual and the ubiquitous presence of digital screens in every shot feel claustrophobic, bringing to mind our age of Zoom anxiety.

Where Diaz’s previous films captured his characters actively struggling against and resisting the tide of history, here they appear paralysed by the spectacle unfolding before them. If the revolution is to be televised in Himala (2020), will we be doomed to mere spectatorship, blinking helplessly—even slavishly—at our screens?

A moment of reprieve arrives at the film’s end in its single wide shot. Chaos continues to reign in the voiceover after Elsa has exposed the truth. We see the actor John Lloyd Cruz watching his phone screen. A fan whirs listlessly in the background. Casually he tosses his phone behind him and leaves the frame.