Review of ‘{if your bait can sing, the wild one will come} Like Shadows Through Leaves’: So Sing Your Song of Re-Enchantment, So See but at an Angle

By Tracey Toh

How do we touch the wild without trapping it? No nature film can escape this paradox: to catch a life on camera is to commit violence, manifested in the vocabulary of “aim”, “shoot” and “capture”. To document is to inevitably disturb the subject and distort the image.

{if your bait can sing, the wild one will come} Like Shadows Through Leaves, by the Migrant Ecologies Project, responds to this dilemma. Their previous installations and exhibitions explored the entwined fates of humans and birds, both displaced by the redevelopment of Singapore’s Tanglin Halt estate. This performative documentary takes a more reflexive turn, challenging the anthropocentric ways of knowing and representing conditioned by cinema.

The film frustrates audience expectations, particularly our reliance on sight in accessing other worlds. Here, aural suggestion is privileged over visual revelation. The shots of unpeopled landscapes operate at a quieter register, so attention settles on the immersive sonic composition. The soundscape evokes a rich ecology, comprising excerpts of interviews, myriad birdcalls, songs and pantuns — the vibrant hum of animacy.

Human voices are left anonymous, while birdcalls are identified by Malay names, rather than scientific terminology. A bird is introduced as Burung Tuwu, named for its distinctive call, koo-oo. The Malay nomenclature reflects a reverence for the more-than-human, allowing the birds to tell us how they wish to be known.

To cultivate intimacy with other lives, we need a mode of engagement that respects their boundaries. Birds are especially elusive, constantly flying beyond the frame. Like Shadows Through Leaves demands too that we see the birds obliquely.

Actual birds are rarely shown, and instead, we see silhouettes of cut-out birds against rough tree bark, dense foliage, shimmering pools of water. Thrice removed from the actuality of the birds — by cut-outs, shadows, movie screen — we are asked to tread gently and keep our distance. Where there is human intervention, it becomes a force of creativity and care. Throughout, the film confesses its own artifice and makes visible the role of the artist. The play of shadows, like wayang kulit, foregrounds the puppeteer’s manipulation. A playful stop-motion of a paper bird hopping reveals the hands that guide the bird’s movements to be as life-like as possible. To represent birds, artists must stay attuned to them.

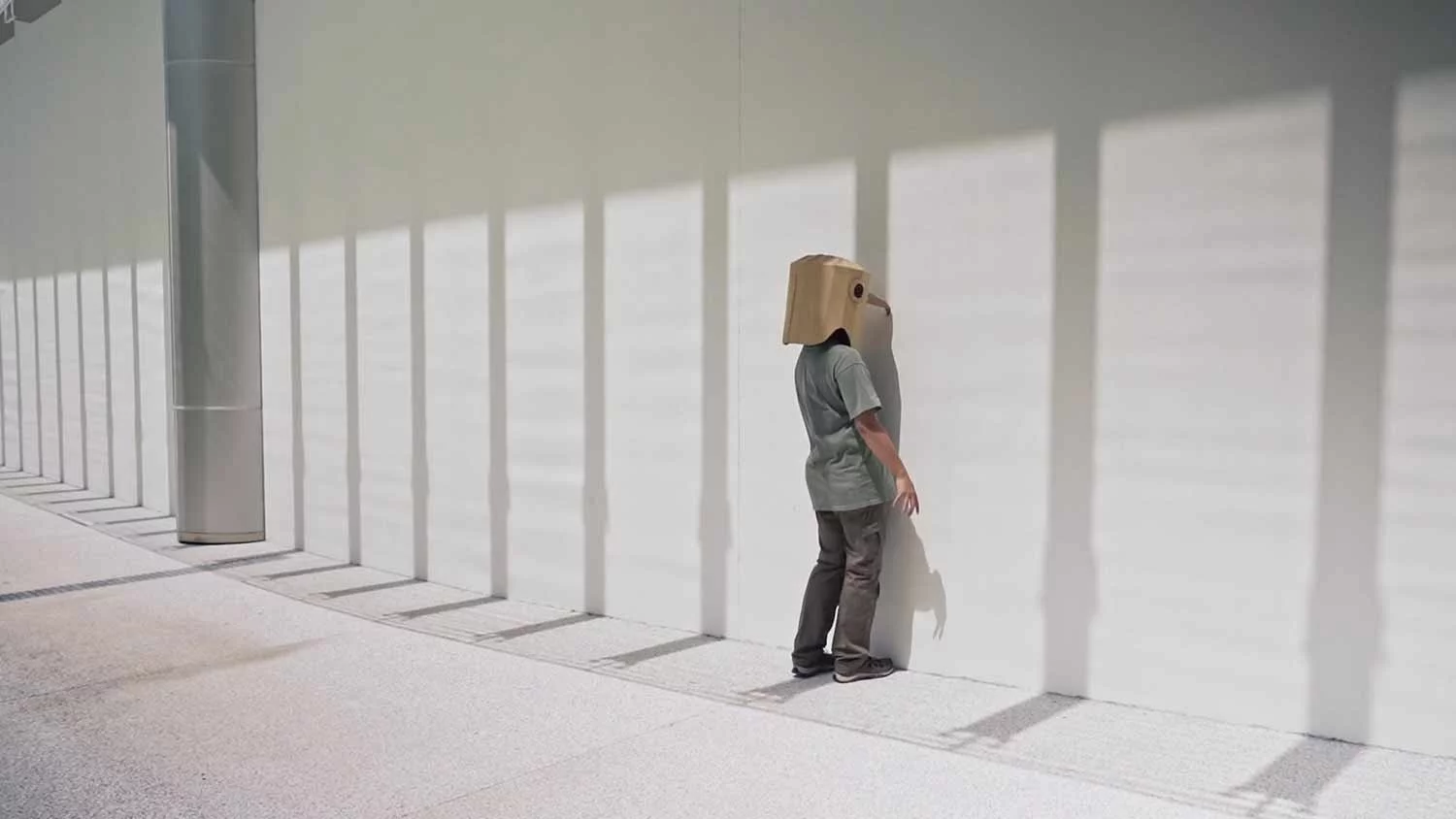

The humans onscreen are all imitating birds, either mimicking birdsong, wielding bird puppets, or donning a cardboard bird head and wandering around. The last seems like an attempt to inhabit the physical body of a bird — that is self-conscious about its futility. The man-bird knocks clumsily into walls, as if coming up against the limits of perception.

Yet, even with these limits, the human and avian are deeply entangled. At the film’s end, a sculpture of housing blocks and bird nests are built inside a tent. Lit up from within, the tent has the effect of a magic lantern, casting long shadows and a spell of re-enchantment.

The sonic textures intensify, shifting imperceptibly between field recordings of birdsong and the human imitation of birdcalls, the result of trained ears and practiced voices. The border between man and bird, reality and representation, dissolves. We are, for a moment, close enough.