The Afterlives of Calamity

By Casidhe Ng

On November 3, 2013, Super Typhoon Yolanda began to form. By 12:00am on November 6, it was deemed a Category 5 typhoon. And by November 7, 8:40pm, Yolanda arrived on the Philippine island of Guiuan, becoming the strongest tropical typhoon to make landfall in world history. These records act as conventional ways for us to understand this disaster. Through them, we trace Yolanda’s origin, intensity, and developmental trajectory, so as to attain greater comprehension.

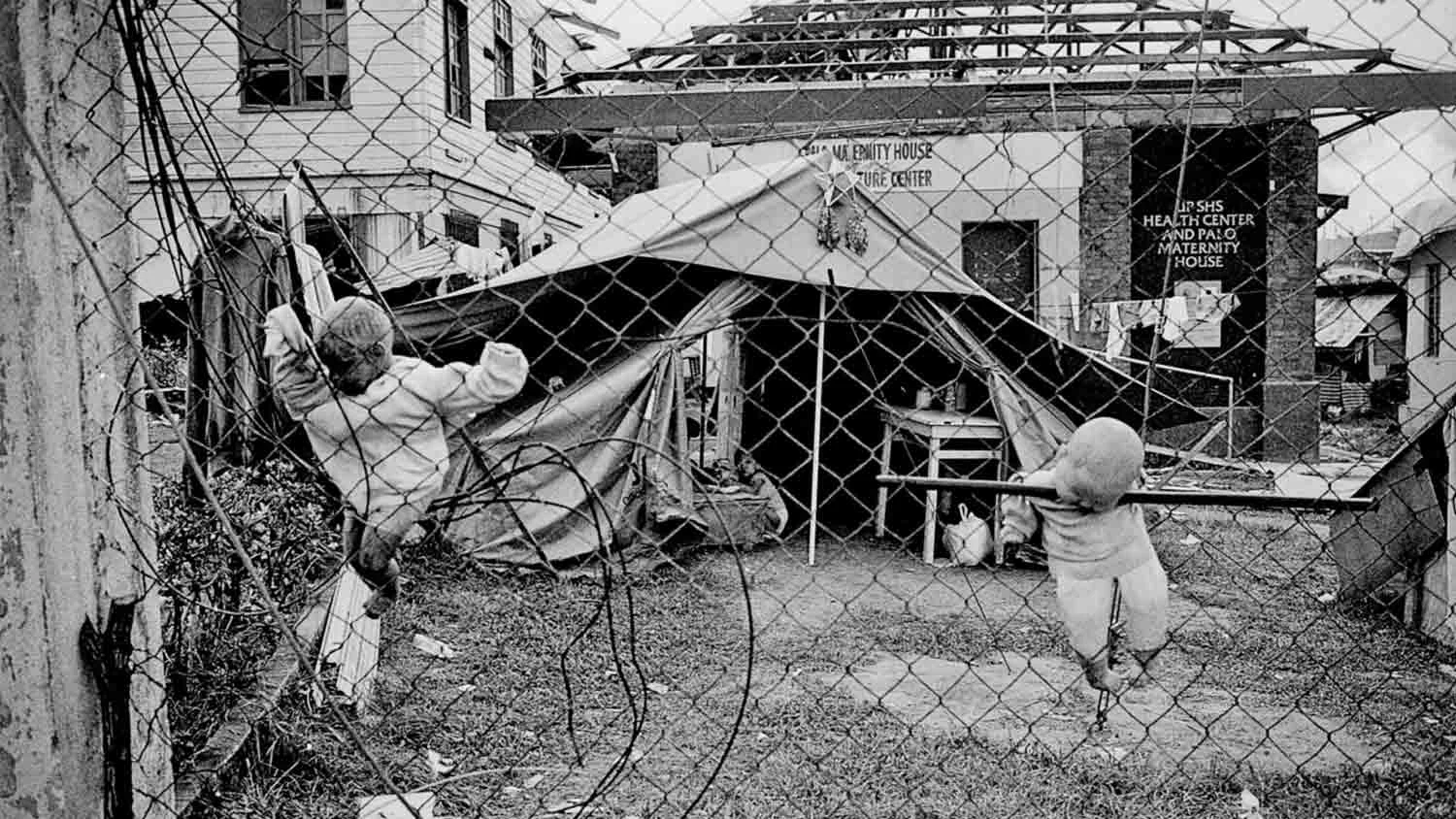

In Joanna Vasquez Arong’s To Calm the Pig Inside, however, detached modes of understanding are pushed aside. Instead of cold, calculated reports, Arong shows us the brutal realities of affected communities. Stitched together from storm footage by James Reynolds, images from photojournalists Villafranca and Thongsa-ard, and voice-over narration by Arong herself, the film extends the palpable melancholia present in the wake of Yolanda, faithfully depicting the harrowing experiences of the victims’ afterlives.

Typhoon Yolanda is of astonishing scale, and unlike any of the natural disasters the Filipino people have experienced before. In one scene, Arong recounts how people turned to myth to explain an earthquake. Lingering on huge waves crashing upon the shore, she narrates, “People told me about Buwa, the pig inside the earth”. “When angry, they say the earth trembles. People then shout ‘Buwa! Buwa!’ during an earthquake to calm the pig inside”. Cutting to a devastated Tacloban City, Arong notes, “But I never heard any stories on how to calm the winds of the typhoon, nor how to prevent storm surge”. The failure of mythology to assuage the people’s fears gestures toward Yolanda’s severe effects. Even within this religious framework, there is no explicable cause or origin, and therefore no possible solution or remedy. Yolanda stands apart from other disasters as a wholly different beast, utterly incomprehensible in the breadth of its destruction.

Yet, the fault of the destruction does not lie on Mother Nature alone. Arong also reveals insidious failures on the level of bureaucracy, placing institutions as equally culpable for the suffering of the Filipino people. A daughter of a Government official spends “funds that were supposed to be for the victims”, while members of an affected town question why the country’s leader had not visited them. They ask, “Isn’t our town part of this country? Isn’t he the president of our town?” The question rings out against Benigno Aquino, calling his relief efforts into question. A silence falls as three villagers stand over piles of rubble, taking cover under the roof of a barely-standing pharmacy. These few shots embody a latent frustration and rage, where the extended desolation is attributed to the failure of national leadership. Through this, the film effectively condemns the inefficiency of governmental response, illustrating the larger (and compounding) issues faced by those struck the hardest.

Finally, the film’s most moving sections neither indicts nor questions, but mourns. Corpses lay unburied in mass graves and graveyards are filled with innumerable crosses. Still, the dead have not departed. The spectral and otherworldly are emphasized through narrated encounters with “restless ghosts”. A driver picks up passengers who are dripping wet, but they vanish into thin air as he turns to address them. Animals, too, respond to the spirits, as village dogs are unable to stop “howling” for periods of time. An image of two dogs in an urban landscape is accompanied by subtle sounds of barking in the distance, layered atop Arong’s voiceover narration. Though seemingly minor in detail, the intentional diegesis thrusts us further into the world of the image. The fog in photos, amplified by the images’ graininess, and the ominous sound of slow-dripping water, construct a Tacloban City haunted by the revenants of the deceased.

Furthermore, spliced between footage of the storm are children’s drawings of the typhoon. Rendered through this childlike lens, Yolanda’s aftermath becomes even more affective. In one sketch, strong winds blow through an already ruined town, populated by houses with torn roofs and countless fallen trees. Another drawing is littered with countless scribbles of the word “Bulig!” (help), yelled by stickmen being swept away by a massive, forceful current. A rising crescendo of flowing waters and torrential winds accompany these images, and the interplay of the aural and visual create a sense of situatedness. We are made privy to the irreversible trauma being inflicted, and the manifestations of horrors that the children have seen. This is Yolanda’s most lasting legacy: not its physical aftereffects, but its influence on the next generation’s psyche.

Arong’s film renders the magnitude of pain, grief and suffering experienced by Yolanda’s victims. Through her meticulous curation of sound, the stills of Tacloban come alive, the loss is keenly felt, and the devastation is made intimate. Speaking of her own childhood, Arong says, “I grew up with stories of ghosts. Even where I live now, [others] say they can hear and feel the ghosts in our home”. To Calm the Pig Inside places the audience in this uncanny state of “hearing” and “feeling”, allowing for the stories of those departed to come through. In spite of their absence, their voices are heard, and it is in listening that we may begin to understand.