Untethering the Past: Radical Applications of the Archive

By Jamie Lee

The archive is a contentious, powerful thing.

In a time where the act of recording has been simplified to the point of frivolity, the use of archival material lends credence to a project. Ripped from the fabric of time and space to slumber comfortably in repositories, archival material has become synonymous with the actual lived past, especially in the presence of highly visible technological markers like the use of black-and-white film stock, or different film formats. We approach this material with the same uncritical complacency that we approach the idea of “data”, and it is this illusive objectivity that makes archival material ripe for exploitation. The ability to project a sense of objectivity is also an opportunity to project an idea of reality, a master narrative.

The inadequacy of archives – and the historical and cultural amnesia that results – is also seen widely throughout Southeast Asia. Heat, humidity, pests and uncooperative governments are anathema to heritage preservation, and the work of archivists becomes a race against time, a race to remember. Archivists and historians in the region are conscious of this connection between memory and power, and how it is used to consolidate political control [1].

The tension that arises from this interplay between memory and power also opens up the archive as a playground for experimentation. By expanding, rearranging and invoking the archive, these three films use extant material to address urgent contemporary issues, rejecting the bifurcation between past and present.

Expanding the archive: Chanasorn Chaikitiporn’s Blinded by the Light

Thai cinema is a distinct cultural product that is deeply linked to Thai social experience and aesthetic history, but also consumed with rabid fervour by regional and international audiences. It has been co-opted as an important part of Thai national identity, keeping in mind the role that the monarchy and the royal family have played in its development – as key investors, patrons and censors [2]. A national love for cinema is a boon to cultural heritage, as this interest is an impetus for remembering and celebrating art, as well as the labour that went into creating it. The issue of whose labour is being remembered, on the other hand, is a central question in Chanasorn Chaikitiporn’s Blinded by the Light.

Archival experimentation can be broadly sorted into the content-specific (what is/isn’t in the archive) and context-specific (the archive’s creation, maintenance, and use). Blinded by the Light falls into the former category, and plays with the multiplicity of historical perspectives, an issue that archives constantly wrangle with.

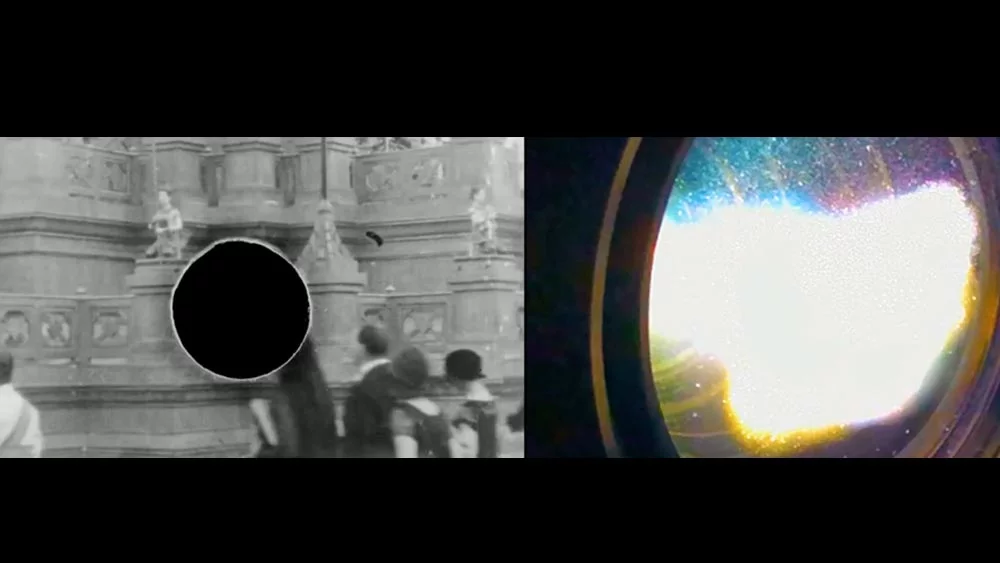

Conceptualised as a split screen film, Chaikitiporn’s work examines the relationship between producers and consumers of art, championing the lesser-heard voices of film crew who have historically served as the backbone of every film production. This message is especially salient in the context of cinema, where critics, audiences, and the media overwhelmingly honour the contributions of directors and their cast, while crew members are lucky to receive any attention at all.

The film expands the archive with its vast assembly of material, contrasting matter-of-fact film production accounts with the glitz and glamour of celebrity culture, in order to make amends for the neglected, working-class men and women who have dedicated their lives to cinema. Each side of the split screen works at its own pace and rhythm, and viewers are faced with the impossible task of conscientiously apprehending an incessant stream of archival and modern footage – including newsreels, archived films and oral history interviews with crew members.

It doesn’t matter if one catches everything, because together, these fragments and perspectives still coalesce into an atmospheric survey of more than a century of cinematic history. There are rare instances, however, between the stretches of frenetic editing, when both sides of the screen synchronise to create a wide vista. It is these instances that capture the beauty of film, as a culmination of individual contributions and individual lives, which, for a brief moment, align to create something much greater than themselves.

Rearranging the archive: Shireen Seno’s To Pick a Flower

The Philippines’ painful relationship with the photographic archive can be traced back to the period of American colonisation (1898–1946), in which photography played an instrumental role in developing and representing scientifically racist narratives, legitimising the regime’s “civilising mission”. American officials stationed in the Philippines, such as Dean C. Worcester, compiled photographs of the Philippines and its natives, especially Igorots and Negritos, to communicate a clear message to the American public: Filipinos were barbarians who desperately needed the United States’ help to progress to a civilised stage[3].

To Pick a Flower rejects this historical use of the archive – as a classification tool to divide and Other. Originally exhibited as part of the group exhibition “Hold the Mirror up to His Gaze: the Early History of Photography in Taiwan (1869-1949)”, the video essay disentangles the relationship between humans and nature, photography and empire. Seno’s languid narration accompanies a slideshow of photographs taken by American botanists during the Colonial era.

Photographs like these – depicting humans, trees, flowers, and landscapes – would originally have been collected, arranged, and disseminated in articles like Worcester’s “American Development of the Philippines”, published in 1903 by The National Geographic Magazine [4], in order to emphasise the underutilisation of the Philippines’ natural resources and justify colonial exploitation [5].

The brilliance of the film lies in Seno’s deviation from this arrangement. She proposes a new way of arranging archival photographs which blends personal storytelling with historical inquiry, and speculates on various relationships – subject-subject, subject-viewer, and subject-photographer.

Lingering on a photograph of four white men standing on a massive tree stump, she narrates, “In these photographs I found of people in relation to nature, men were usually photographed as conquistadors, exerting their power over trees.” For a photograph of a bride standing next to a potted plant, she offers the insight, “An air of uncertainty abounds, could it be that her groom is running late, or has failed to show up? Is she hesitant to enter into marriage with him, or at all? Or perhaps, she is so uncomfortable and just couldn’t wait for this photograph to be taken.”

The duration between photographs is also erratic, and at many points viewers are left to gaze at a blank screen, waiting for the next slide – a thoughtful pause for both viewer and narrator to meditate on the meaning of each one. This arrangement teases out the humanity and the emotion from these captured moments, extending subjects an aspect of consideration that they were never offered, and achieving an unusual balance between the sentimental and critical.

Invoking the archive: Lav Diaz’s Himala: A Dialectic of Our Times

Attempts to preserve the Philippines’ cinematic heritage have also had to reckon with its tumultuous political history, marked by unstable presidential administrations. The first state-funded film archive, the Film Archives of the Philippines, was founded in 1982 during the Marcos regime, but quickly shut down after the regime was ousted in 1986. A new film archive was only founded twenty-five years later, and this gap between institutions is filled with accounts of cultural neglect and loss. It is estimated that out of a total of 8,000 Filipino films created since 1897, only 3,000 survive to this day. In recent decades, film archivists and historians have had to work tirelessly to combat the cultural amnesia fostered by state negligence [6].

In this context of state-induced cultural amnesia, remembering becomes an act of political resistance. This idea is exemplified in Lav Diaz’s Himala: A Dialectic of Our Times, whichleverages on the eponymous film’s power as a Filipino cultural marker.

Restored and remastered by ABS-CBN’s Film Archives and Central Digital Lab in 2012, the original Himala (1982) tells the story of Elsa (played by Nora Aunor), a girl who claims that an apparation of the Virgin Mary has given her miraculous healing powers. Towards the end of the film, she confesses to her fraud —

“There is no miracle! Miracles are in people’s hearts, in all our hearts! We are the ones who make miracles! We are the ones who make curses, and gods!”

The film has been heralded as one of the greatest works in Filipino cinematic history, and its final act delivers a humanist critique of blind faith and the apathy that results from it. Himala: A Dialectic of Our Times invokes Elsa’s plea through a simple execution, consisting of shots of twenty-eight individuals watching and reacting to her final speech. The viewer never gets to see this iconic scene; instead, the film is tied together by the reactions of the cast, who have, in all likelihood, watched Himala before.

The cast offer mixed reactions – some have their brows furrowed, deeply engrossed; others appear distracted, or tired. Most are filmed in their homes, using a lo-fi setup necessitated by COVID-19 restrictions. Despite all attempts at creating a realistic mise-en-scène, the viewer is never actually sure as to whether these are genuine reactions, and this undercurrent of ambiguity elevates the film from just being a naïve call to arms.

This is perhaps fitting, as the relationship between cinema and reality has always existed in ambiguity. No doubt, the trajectory of human society has been irreversibly shaped by the moving image, but its influence on our lives, our hopes, and our dreams is unmeasurable. While restoration gave Himala a new lease on life, countless other Filipino films have been lost, whether to incompetence or the unsympathetic march of time. Diaz’s film underscores the crucial role of cinema and, by extension, the archive, in wresting control over our own realities.

References

[1] Karabinos, M. (2015). The Role of National Archives in the Creation of National Master Narratives in Southeast Asia. Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies, 2(1), 4, pp. 1-3.

[2] Sungsri, P. (2004). Thai cinema as national cinema: an evaluative history (Doctoral dissertation, Murdoch University), p. 31.

[3] Rice, M. (2011). Colonial photography across empires and islands. Journal of Transnational American Studies, 3(2), pp. 1-7.

[4] Rice, M. (2011). Dean Worcester’s Photographs and American Perceptions of the Philippines. Education About Asia, 16(2), p. 30.

[5] Rice, M. (2011). Colonial photography across empires and islands. Journal of Transnational American Studies, 3(2), p. 6.

[6] Lim, B. C. (2013). A brief history of archival advocacy for Philippine cinema. 2013 PHILIPPINE CINEMA HERITAGE SUMMIT: a report, pp. 14-16.