Sidestepping Skipping Through a Chaotic World

By Teo Xiao Ting

As a film festival occurring in this time, whimsicality seems almost necessary in order to break the tedium and stress that the pandemic has surfaced. Or perhaps even for survival, as the climate crisis and its associated crises come closer in view. To take everything head on all the time is exhausting, leaves little room for breathing. No doubt, films that unflinchingly witness our current and upcoming crises as they are are essential, but so are films that allow themselves an adjacent view of the world despite tragedies of various magnitudes. Whether this presents itself in an offbeat, silly manner, or the absurdity of complete abstraction, these sideway glances perhaps gives relief to the tunnel vision that trauma sometimes forces us into. I am thinking specifically of The Cup by Mark Chua and Lam Li Shuen, A Trip to Heaven by Duong Dieu Linh, and Estate by Lin Htet Aung.

The furthest from a realistic representation of this world is perhaps Estate, which comprises almost entirely grey bars in varying shades. It is about grief, about a son grieving his dying father. So writes the synopsis, so says the narrator. But it is also about the inarticulate nature of intense emotion. There is no image sufficient for the anxieties and resentments that a looming death of one’s immediate family member can surface, and so Lin does away with most of it. Throughout the film, the clearest glimpses we get of the world the narrator resides in are peripheral. A flash of the image of Buddha, found sounds of a leaking faucet, footsteps on what sounds like parquet flooring. These flashes ground the film in the material world, as we wade through the narrator’s emotional landscape, following him around the family home. A light grey flittering across bars of darker grey is perhaps someone opening the blinds of a previously dark room. An almost black spectre cutting through the same light hues is perhaps a person walking across the room, casting shadows as they disrupt the flow of light. All movements are severely abstracted, made concrete only through an intricate soundscape sketched from objects such as the creak of a door opening, or the flick of a lighter. Despite the visual tedium of grey that seems to sand down the narrator’s intense emotions towards his father, his voice betrays the conflicting emotions of resentment and inevitable care he feels, as he blurts how “his legs keep coming back to [his father]” against his will.

In Estate, tragedy is unspectacular – painfully and casually so. Where we expect the hefty weight of grief, we are confronted with flatness. The first few words uttered by the narrator augments this inescapable tepidity – that his father’s ways “repeats itself, repeats himself”. It allows another path towards understanding and experiencing grief and its related tediums, a path that is decidedly less concerned with giving it concrete form. A path that does not care to explain or delineate the contours of grief, but to present it as it is felt day to day. There is an uncanny resonance with how at this point, the struggle to keep oneself afloat with the flurry of uncertainty brought forth by the most recent pandemic becomes almost tepid but no less intense. Because Estate is so outrageously deviant from realistic representations, the grey bars became a gateway for another kind of being, understanding. Trauma and its inflictions are allowed to become mere bars of grey that gives me a moment’s respite from a relentlessly realistic confrontation.

This delicious tepidity is also carried forth by The Cup, where we follow a human figure across a day as he tries to make a better-tasting cup of coffee. With a plasticine head topped with a potlid, our protagonist has lightless headlamps for eyes and a normal pair of hands. A trace of normalcy dangling at the edge of silly everyday items masquerading as flesh. His day is like any other day, resonant with how the days blur into each other through the enforced isolation that we have been experiencing, in order to curb the spread of COVID-19. As we follow him through his day, his flesh becomes a kettle, a coffee machine, coffee bean dispenser. The kettle on his coffee table becomes irrelevant. The man’s humanity is beyond a doubt, though. He bleeds after trying to shave himself clean of the curious black fronds that took it upon themselves to grow on his skin like fungus midway the film, and he flinches to remind us that he feels pain, too, despite his wayward appearance. The Cup doesn’t take us on a trip to dehumanise, but to give a tangential view of the man as he perhaps feels to be. Something between a human and a self-sufficient machine. Through his eyes, we see not his soul, but the mouth of a coffee pot as he unscrews it to pour a steady stream of black coffee. A stark contrast to how we typically assume body parts to look like, The Cup’s protagonist allows us a view that abandons linear logic in favour of lateral associations and emotional resonance.

And it is perhaps a more accurate portrait of how a lone individual tries to navigate his days through micro routines in a time of extreme uncertainty and isolation than a documentation of an actual uncle moving through his day. The protagonist is indeed an uncle, reminiscent of a typical Singaporean taxi uncle who sits at a kopitiam sipping a cup of kopi and smoking a cigarette as he takes a break, whistling old tunes as he props his leg up on a chair. While he never did make this sequence of movements in the film, in his conversations with his shadow in Teochew and Cebuano, I can almost see it in my mind’s eye, through his crass lilt complaining about his coffee (made from his own body) and his irritation (unsentimental and matter-of-fact) at yet another work day. Throughout the film, there is no dramatic climax, only an accumulation of banal crises as the protagonist continuously tries to make his cup of coffee taste better. But there are bright moments, presented in a delightfully quiet manner. As we watch him lay down, seemingly photosynthesizing, there is a sense of respite from his previous exasperated attempts at coffee-making. A moment’s rest, that continues as we approach the end of the film, as he reaches out of his apartment when it starts to rain. When he pops his head out of his neck to catch rainwater, the previously consistent rhythm of his day was disrupted, seemingly resolving his struggle of making a better cup of coffee as the rainwater washes down his head. Despite the steady dread of everyday life repeating itself in an endless cycle, the reality presented in The Cup resists simple routines for surreal lightness instead.

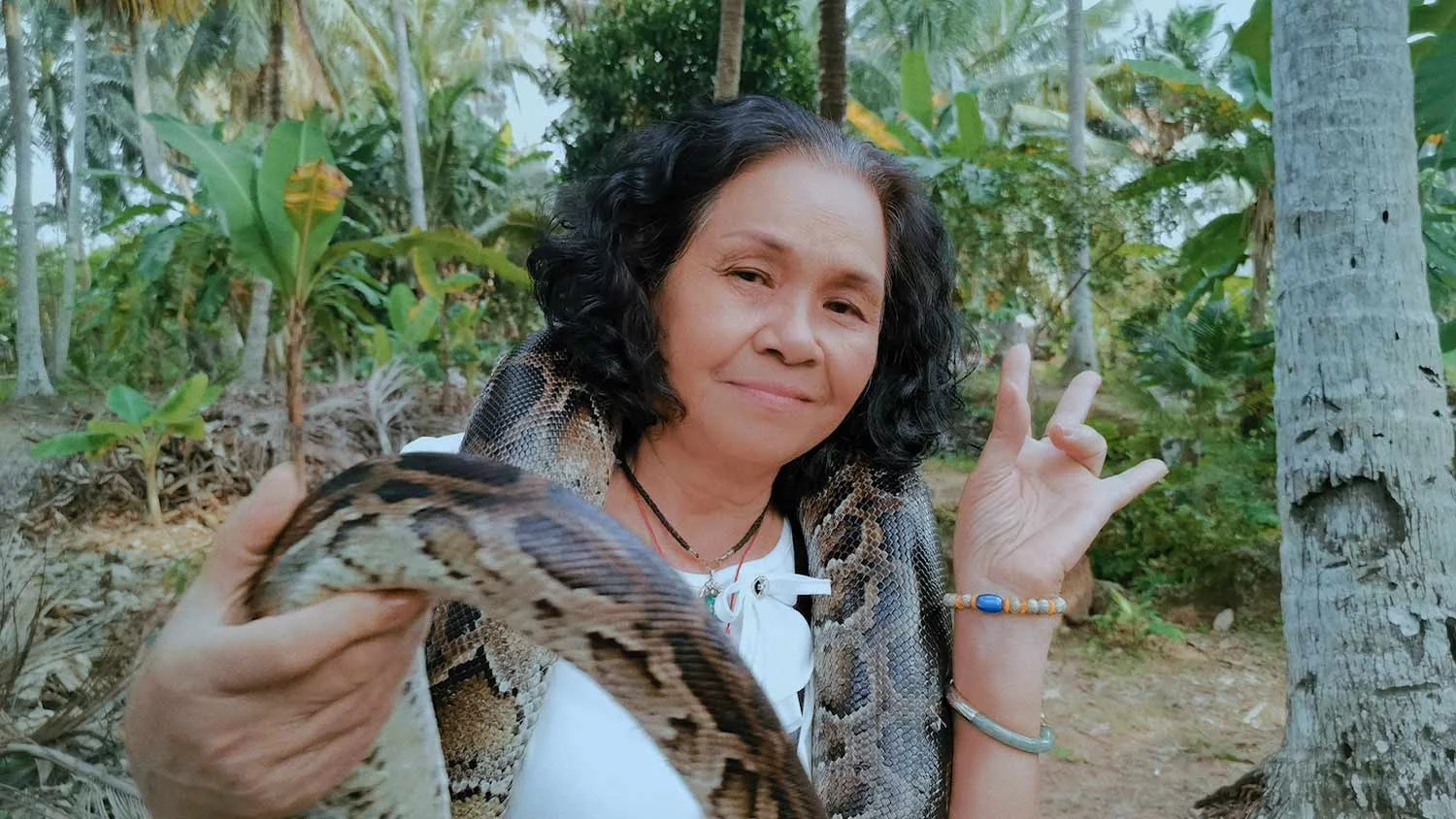

Augmenting the ride that The Cup brought me on is A Trip to Heaven, which follows a Mdm Tam as she joins a tour with her friend to explore presumably the afterlife. Buoyed by highly saturated candy colours, we bounce onto the bus with Mdm Tam as she confesses to her friend that her first love is also on the tour with them. The excitement of youthful infatuation creates a vague tension as they are all dead and on the way to elsewhere. Is death an excursion? Well, yes. The tour group breezes through attractions such as a “stairway to heaven”, and we see other tourists (dead people?) taking selfies in front of it before ascending and leaving this plane. The same way Estate presents grief without explicitly portraying it, A Trip to Heaven breaks away from the typically grief-laden narrative of afterlife and death, bringing us on a ride that is undeniably playful and funny, even enjoyable. Can the aftermath of tragedy, which is what death is commonly associated with, be enjoyable? Be an adventure? As Mdm Tam and the tour group gather round a campfire dancing and singing, the answer leans towards yes. There seems to be no regrets, even though at the start we see Mdm Tam and her friend arguing about whose grandchildren is more loving, more caring towards themselves. There is no hesitation or even regard for how they will survive them. Only a fun trip, and an implicit trust that those who are living will be fine. As the film ends, the tour group ascends up the stairs one by one, not with despair or pain, but a celebration, almost like a graduation ceremony.

Collectively, these three short films confront heavier topics such as grief, ennui, and death in ways that do not perpetuate the weight that they hold. They provide an alternative view of how these experiences are felt, can be felt, through the screen, which we have been all too familiar with in a time where in-person interactions are discouraged. Instead of reactions to these tragedies, they seem to whisper gently, excitedly even, that if we cannot escape disaster, we might as well prance our way through it.